What the Beats were about

BY LOUIS MENAND

The New Yorker October, 2007

“The social organization which is most true of itself to the artist is the boy gang,” Allen Ginsberg once observed. It’s a sentiment that Frank Sinatra would have appreciated. The time of “Howl” and “On the Road” was also the time of “Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely” and the original “Ocean’s Eleven,” and although by many measures a taste for the product of North Beach is incompatible with a taste for the product of Las Vegas, the Beat Movement writers and the Rat Pack entertainers were shapers of a similar sensibility.

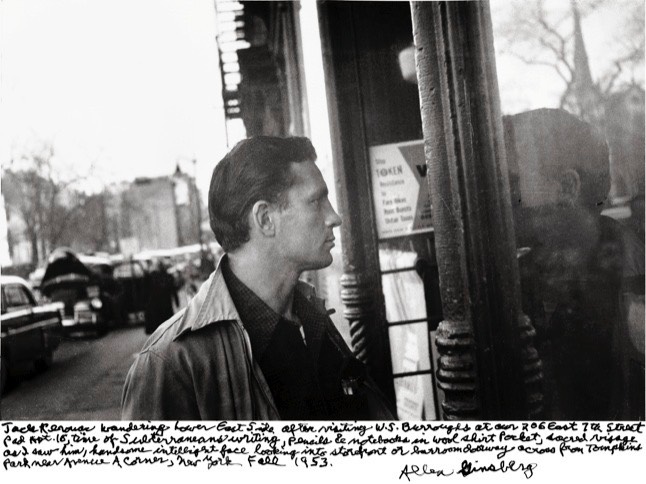

When “On the Road” came out, in September, 1957, it was praised in the New York Times as the novel of the Beat Generation, equivalent in stature and significance to “The Sun Also Rises,” the novel of the Lost Generation. The book was a best-seller, and it made Jack Kerouac, who had worked on it for ten years, a celebrity. It is sometimes said of Kerouac that fame killed him—that he was driven crazy by being continually addressed as the spokesman for a generation and by endless unwelcome requests to explain the meaning of the term “Beat.” Kerouac was certainly undone by something. After the success of “On the Road,” he continued to write at a manic pace, as he always had, but he became a suicidal alcoholic, and he died, of a hemorrhage caused by acute liver damage, in 1969, at the age of forty-seven. (He had by then written more than twenty-five books.) The notion of the Beat Generation was hardly thrust upon him, though.

“Beat” is old carny slang. According to Beat Movement legend (and it is a movement with a deep inventory of legend), Ginsberg and Kerouac picked it up from a character named Herbert Huncke, a gay street hustler and drug addict from Chicago who began hanging around Times Square in 1939 (and who introduced William Burroughs to heroin, an important cultural moment). The term has nothing to do with music; it names the condition of being beaten down, poor, exhausted, at the bottom of the world. (It’s used often in this sense in “On the Road.”) In 1948, Kerouac is supposed to have remarked, in a conversation with the writer John Clellon Holmes, “You know, this is really abeat generation” (followed by a spooky “only the Shadow knows” laugh), and Holmes thought enough of the phrase to use it as the working title of a novel, eventually published as “Go,” and to write an article for the Times Magazine, in 1952, called “This Is the Beat Generation,” in which he credited Kerouac with the term. (The article was solicited by the man who, five years later, wrote theTimes’ review of “On the Road,” Gilbert Millstein.)

Holmes wasn’t referring to a movement. He was referring to the Cold War generation, which, he said, had been disillusioned by the war, the bomb, and the “cold peace,” but was obsessed with the question of how life should be lived. Holmes thought that Beats were optimists, risk-takers, seekers—young people with “a desperate craving for belief.” The article popularized the concept, and Kerouac began using it himself. “Beat Generation” was one of his early titles for “On the Road.” (Another was “Shades of the Prison House.”) After the book came out, he wrote a play called “Beat Generation,” an article for Esquire on “The Philosophy of the Beat Generation,” and another for Playboy on “The Origins of the Beat Generation,” in which he added “beatific” to the meanings of “Beat.” In interviews up to the end of his life, he talked about his conception of the Beat Generation, and the literary movement associated with it, proudly, affectionately, and defensively. In his final appearance on television, a falling-down-drunk performance on William F. Buckley’s “Firing Line,” he insisted that his idea of beatness had nothing to do with the hippies (whom he despised).

It’s true that the Beat writers were caricatured and abused. In the literary world, academic critics, whose aesthetic was all about form and restraint, ignored them, and the New York intellectuals, whose ethic was all about complexity and responsibility, attacked them. Irony was the highbrow virtue of the day, and the Beats had none. This response probably did matter a little to Ginsberg and Kerouac. They were Columbia boys. They had genuine literary aspirations, and they wanted to be taken seriously. On the other hand, they could hardly have lived in hope of the approval of people like Diana Trilling and Norman Podhoretz.

In the entertainment world, “Beat” was transmuted into “beatnik,” a word invented, in 1958, by the San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen. The term derives from Sputnik, which was launched into space a month after the publication of “On the Road.” (Why is a beatnik like Sputnik? They are both far-out.) The type was made immortal by the character Maynard G. Krebs on the television series “The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis”—a goateed, bongo-playing slacker who calls people “daddy-o.” But lampooning is merely the price of mass attention.

Satire and polemic are, on some level, defensive. It’s possible that something about the Beats simply made people uncomfortable. For the nineteen-fifties images of the Beat—Partisan Review’s bohemian nihilist and Hollywood’s hip hedonist—are almost complete inversions of the character types represented in “On the Road.” The book is not about hipsters looking for kicks, or about subversives and nonconformists, rebels without a cause who point the way for the radicals of the nineteen-sixties. And the book is not an anti-intellectual celebration of spontaneity or an artifact of literary primitivism. It’s a sad and somewhat self-consciously lyrical story about loneliness, insecurity, and failure. It’s also a story about guys who want to be with other guys.

The Beat Movement had a male muse. This was, of course, Neal Cassady, the protagonist of both “On the Road,” where he is Dean Moriarty, and “Howl,” where he is “N. C., secret hero of these poems, cocksman and Adonis of Denver.” Cassady also figures in several of Kerouac’s other books—five of Kerouac’s road novels are being published this fall by the Library of America ($35) in a volume edited by Douglas Brinkley—and his iconic presence went beyond the Beats. He became a friend of Ken Kesey, and he was the driver on the Merry Pranksters’ famous bus trip, the subject of Tom Wolfe’s “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.” The Grateful Dead wrote a song about him. He is the Lou Andreas-Salomé, the Alma Mahler Gropius Werfel, of postwar American culture.

Cassady was an uncanny cross between James Dean and W. C. Fields—a screwup with a profile, a stud with an endless supply of goofy gab. There is sufficient testimony concerning his sexual endowment to overcome the skepticism normally advisable on that topic. Some people who knew and liked him called him a con man (and many people, including Burroughs, disliked and avoided him), but this seems misleading. Cassady was a serial seducer, and, therefore, inveterately untrustworthy. He grew up on the Denver streets—his father was a wino—and he learned to cope by relying on his enormous energy, adaptive wit, and good looks. He charmed people in order to get what he needed, and he was generally in need of something. On the other hand, the people he charmed generally needed something from him—sex or companionship or good times. And Cassady had no material ambitions. He was content to get by, and although he had three wives in rapid succession, and juggled his attentions between them and assorted casual girlfriends, he was intermittently serious about all of them. Everything about Cassady was intermittent. He had a kind of sociosexual A.D.D.

Kerouac and Ginsberg met Cassady in New York City in 1946, around Christmastime. They were introduced by Hal Chase, a Columbia anthropology major from Denver. (Chase appears as Chad King in “On the Road.”) Cassady was twenty. It was his first trip to New York, and he was accompanied by his sixteen-year-old wife, LuAnne (Marylou in “On the Road”). Cassady claimed to have stolen five hundred cars when he was a teen-ager, all for joyrides, and he had spent some time in reform school, where he developed an enthusiasm for books. He came to New York because he dreamed of attending Columbia (this didn’t happen) and being a writer (this only sort of happened), and he befriended Kerouac and became Ginsberg’s lover because he thought that they could help him. Kerouac befriended Cassady because he wanted to write a novel of the road, and he thought that Cassady could be the basis for a good character.

Fundamentally, “On the Road” is autobiographical. It’s a report—with pseudonyms (for legal reasons) and elisions (mostly for length reasons)—of four long-distance trips that Kerouac made between 1947, when he bused and hitchhiked by himself from New York to Denver, and 1950, when he drove with Cassady and another friend from Denver to Mexico City. (Kerouac’s real-life travels are the subject of “Jack Kerouac’s American Journey,” by Paul Maher, Jr.; Thunder’s Mouth; $15.99.) Kerouac is quite explicit about it: the trips in “On the Road” were made for the purpose of writing “On the Road.” The motive was not tourism or escape; it was literature.

In fact, Kerouac began the book before his first trip with Cassady, which they took in the winter of 1948-49. He kept detailed journals, and he struggled for a long time to find the proper form for a narrative. He started by inventing fictional characters with backstories, and it was three years before he finally dropped the idea of a conventional novel and simply wrote down what had happened. This was the celebrated scroll, a continuous length of paper, a hundred and twenty feet long, on which Kerouac typed the first complete draft of the book in three weeks in April, 1951, with the assistance of his second wife, Joan Haverty, and a lot of coffee. (Not, as legend has it, Benzedrine—which is not to say that Kerouac was a stranger to amphetamines.) He immediately retyped the book on regular paper, and then spent six years revising it. Howard Cunnell’s useful edition, “On the Road: The Original Scroll” (Viking; $29.95), makes it clear that, despite his later talk about the spontaneous method of composition, Kerouac did not create the published book in a single burst of inspiration. It was the deliberate and arduous labor of years.

The literature of the road is immense. (One work not often mentioned as a possible influence on Kerouac is Woody Guthrie’s autobiography, “Bound for Glory,” which was published in 1943. It’s more Okie than jivey, but it aspires to the same beatness and the same lyricism of place.) “On the Road” is as self-consciously a work of literature as “À la Recherche du Temps Perdu”—and Proust was a writer whom both Kerouac and Cassady emulated, someone who turned his life into literature. Kerouac read widely and intelligently: he knew what he was doing when he put the scroll into the typewriter, and, just as important, he knew what he was not doing, what kind of book he was not writing—just as (to take a common and apt contemporary comparison) Jackson Pollock knew that he was not making an easel painting, with all the aesthetic assumptions that that implied, when he put a canvas on the floor and poured paint on it.

Kerouac credited the inspiration for the scroll to Cassady—specifically, to a long letter, supposedly around thirteen thousand words, that Cassady wrote over several days (he was on speed) in December, 1950. This is known as the “Joan letter,” because its ostensible subject is a girlfriend of Cassady’s named Joan Anderson. But the letter, or the portion of it that survives (the original is lost, a holy Beat relic), is actually a hyper, funny, uninhibited account of Cassady’s sexual misadventures with a different girlfriend. It has no stylistic pretensions; it’s just a this-happened-and-then-that-happened piece of personal correspondence. Kerouac was knocked out by it. “I thought it ranked among the best things ever written in America,” he wrote to Cassady. It had the vernacular directness and narrative propulsion he was looking for, and it gave him the impulse he needed to tape his scroll together and get a complete draft on paper. He saw that this-happened-and-then-that-happened had literary possibilities, and the scroll was a way of forcing himself to stick to this vision. (A little later, Frank O’Hara made poems using the same theory. “I do this, I do that” is how he described them.) The scroll was therefore a restriction: it was a way of defining form, not a way of avoiding form. In religious terms (and Kerouac was always, deep down, a Catholic and a sufferer), it was a collar, a self-mortification. He did, after he finished the scroll, go back and make changes. But first he had to submit to his discipline.

Nostalgia is part of the appeal of “On the Road” today, but it was also part of its appeal in 1957. For it is not a book about the nineteen-fifties. It’s a book about the nineteen-forties. In 1947, when Kerouac began his travels, there were three million miles of intercity roads in the United States and thirty-eight million registered vehicles. When “On the Road” came out, there was roughly the same amount of highway, but there were thirty million more cars and trucks. And the construction of the federal highway system, which had been planned since 1944, was under way. The interstates changed the phenomenology of driving. Kerouac’s original plan, in 1947, was to hitchhike across the country on Route 6, which begins at the tip of Cape Cod. Today, although there is a sign in Provincetown that reads “Bishop, CA., 3205 miles,” few people would dream of taking that road even as far as Rhode Island. They would get on the inter-state. And they wouldn’t think of getting there fast, either. For although there are about a million more miles of road in the United States today than there were in 1947 (there are also two more states), two hundred million more vehicles are registered to drive on them. There is little romance left in long car rides.

In fact, the characters in “On the Road” spend as short a time on the road as they can. They’re not interested in exploring rural or small-town America. Speed is essential. The men rarely even have time to chase after the women they run into, because they’re always in a hurry to get to a city. A lot of the book takes place in cities, particularly New York, Denver, and San Francisco, but also Los Angeles, New Orleans, and Mexico City. Even there, the characters are always rushing around.

The bits and pieces of America that the book captures, therefore, are snapshots taken on the run, glimpses from the window of a speeding car. And they are carefully selected to represent a way of life that is coming to an end in the postwar boom, a way of life before televisions and washing machines and fast food, when millions of people lived patched-together existences and men wandered the country—“ramblin’ round,” in the Guthrie song—following the seasons in search of work. Robert Frank’s photographs in “The Americans,” taken between 1955 and 1956 and published in Paris in 1958 and in the United States a year later, with an introduction by Kerouac, held the same interest: they are pictures of a world not yet made plump and uniform by postwar affluence and consumerism.

The sadness that soaks through Kerouac’s story comes from the certainty that this world of hoboes and migrant workers and cowboys and crazy joyriders—the world of Neal Cassady and his derelict father—is dying. But the sadness is not sentimentality, because many of the people in the book who inhabit that world would be happy to see it go or else are too drunk or forlorn to care. They do not share the literary man’s nostalgie de la boue; they are restless, lonely, lost—beat. “There ain’t no flowers there,” says a girl whom Sal Paradise, the Kerouac figure, tries to pick up in Cheyenne by suggesting a walk on the prairie among the flowers. “I want to go to New York. I’m sick and tired of this. Ain’t no place to go to but Cheyenne and ain’t nothin in Cheyenne.” “Ain’t nothin in New York,” Sal says. “Hell there ain’t,” she says. She wants to get in the car, too.

And the car is the place to be. Why? The obvious answer is that nothing happens in the car. Everyone has an irresistible urge to get to Denver or San Francisco or New York, because there will be work or friends or women there, but, after they arrive, hopes start to unravel, and it’s back in the car again. The characters can’t settle down except when they are nowhere in particular, between one destination and the next. But they want to settle down somewhere in particular. They are not sociopaths or radicals—as John Leland argues in “Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of ‘On the Road’ “ (Viking; $23.95). Their crimes against the establishment consist of speeding, shoplifting, and a minor bout of car stealing (all right, a little illegal drug use, too). They fear and dislike cops, as most people without much money do; other than that, they are not especially antisocial.

They are not hipsters, either, cats too cool for life in suits. There is nothing cool about Dean or Carlo Marx (the Ginsberg character, Karl converted into a Marx Brother). The characters marry and get legally divorced; they take jobs and quit them; they talk about Dostoyevsky and Hemingway and write novels and poems and hope for recognition. The narrator lives with his aunt, who sends him money when he needs a bus ticket home. Otherwise, he draws on his G.I. benefits. A middle-class life with a house and a wife and kids is what Sal wants, and what Dean would want, too, if he could stop getting in his own way. As Kerouac later insisted, it’s a mistake to read this as an anticipation of the counterculture.

The car is also a male space. The women who end up being driven in (never driving) the car are either shared by the guys (Marylou, for example, whom Dean hands off to Sal, as Cassady handed off LuAnne to Kerouac) or abandoned (as happens to the character Galatea Dunkel, and as happened to her real-life counterpart, Helen Hinkle). But the car is not an erotic space. Driving is a way for men to be together without the need to answer questions about why they want to be together. (Drinking is another way for men to be together, and there is a lot of drinking in “On the Road.” There is a lot of drinking, period.) In this sense, “On the Road” is a little like another sensational road novel of the time: Humbert and Lolita drive obsessively back and forth across the continent because that is the only public way for them to be together. As long as they’re driving, they’re not doing anything they shouldn’t be doing.

But maybe we should not understand the sexual themes in “On the Road” too quickly. Maybe the best thing to say about those themes is that they are murky and underrealized, not entirely within the author’s control. Sal has a crush on Dean, in the way that attractive but insecure men can form attachments to gregarious and self-confident men. Sal gets close to women vicariously by being closer to Dean than Dean’s women are (until he, too, gets dumped, in Mexico City). This is perfectly consistent with the “Ocean’s Eleven” genre of buddy stories: there is always a dame, but the real bond is between Brad and George. They have something with each other that neither could have, or would care to have, with a woman.

How much farther do we want to go, though? Kerouac was certainly infatuated with Cassady. Partly this was a genuine fascination shared by many; partly it was his belief that in Cassady he had found a perfect foil, in literature and in life, for his own moody and self-absorbed response to experience. Was he in a state of unavowed love? The sexual world of the Beats is, to say the least, confused. There is, right near the top among Beat legends, the strange story of Kerouac and Ginsberg’s Columbia friend Lucien Carr, who, in 1944, killed his gay stalker (and former scoutmaster), David Kammerer, in Riverside Park and got Kerouac to help conceal the evidence. Kerouac was arrested as a material witness, and he married his first wife, Edie Parker, in part so her family would put up bail money. (The marriage was annulled after two years.) Kerouac had a tendency to get involved with his male friends’ former girlfriends; his longest and closest relationship was with his mother. He was living with her, in Florida, when he died. (She is the aunt in “On the Road”—a more respectable relative for a grown man to be dependent on.) Burroughs was homosexual, but lived with and had children with his common-law wife, Jane Vollmer, whom he loved and whom he shot dead in a drunken game of William Tell, in Mexico City, in 1951. Ginsberg was attracted to straight men: his frustration with Cassady was repeated throughout his life. Peter Orlovsky, his longtime partner, was basically straight. And Cassady was a priapic pinball machine whose sexual bouncing around was plainly from desperation. No one would want to be like that. The Beats were not rebels; they were misfits.

“On the Road” does not cross over into this territory. In the scroll version, the sexual relation between Carlo and Dean is explicit, but that material was eliminated. The sexuality of the book that we have is straight, and mostly male. The book is not really about sexuality; it has a slightly different subject, which is masculinity. There is no good cultural model, in the period in which the story is set, for the kind of men the characters are—as there was no model for Kerouac and Ginsberg themselves. This was the reason that Kerouac became so embittered by the caricatures of the Beats: they played off stock conceptions of masculine types—the hip anarchist, the leotard-chasing, jazz-fiend tea-head, the swaggering barfly, the hot-rodder, the cruising delinquent. Kerouac was none of these things. He was shy with women; he was devoted to his mother and his friends; he was a workaholic (as well as an alcoholic); and he didn’t like to drive. His drinking was self-medication; it was not for fun. He was not a macho anti-aesthete. He was the opposite, a poet and a failed mystic. He was what in the nineteen-fifties was referred to as a “sensitivo.” This was the demon that he wrestled with. And this is the point at which the thematic preoccupations of “On the Road” meet the style of “On the Road”—the lyrical, gushing, excessive prose.

“Beautiful” is a word that some women used to describe Kerouac. Before he became bloated by drink, he was rugged, too—he had been recruited to play football at Columbia—and he had a husky baritone. He spoke with a Boston accent (he was from Lowell), and he was excruciatingly self-conscious. That was one of the sources of his perpetual discomfort, but when he was sober it added to his appeal: he was virile and he was shy. In 1959, he appeared on television, on “The Steve Allen Show.” Steverino was a jazz buff who used to noodle around on a piano while he interviewed his guests (an unbelievably annoying routine). He liked Kerouac, and Kerouac seemed less than usually guarded with him. After they chatted, a little awkwardly, two men in jackets, Kerouac read the last paragraph of “On the Road,” while Allen contributed background riffs on the piano:

In Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let the children cry, and tonight the stars’ll be out, and don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.

It is sensitive and it is earnest, a performance of one of the most difficult emotions to express, male vulnerability. It’s not too hard to imagine Sinatra intoning this passage, snapping his fingers quietly to the musical accompaniment. There is something risky and exposed about Kerouac’s reading, as there is about Kerouac’s prose. The Beats were men who wrote about their feelings.

Years ago, I taught in a Ph.D. program at the City University. One semester, Allen Ginsberg, who was affiliated with one of the CUNYcolleges, offered a graduate seminar. He was nearly seventy, small, neatly dressed in jacket and tie and gray flannel pants, totally adorable. He once sweetly sidled up to me and said, “I heard that you are teaching Gertrude Stein.” Then, in a lower voice, “I have some tapes of Gertrude Stein reading”—as one might say, “I have some photos of Greta Garbo in the nude.” I said to the graduate students that I thought it must be amazing to take a seminar with Ginsberg, to be around someone who had been around so much. “Nah,” they said. “He just keeps saying that Kerouac is the most important American writer.” Possibly, they didn’t think that knowing a great deal about Kerouac was going to give them much of a professional edge.

Possibly, they were right. “Lolita” is in the canon; “On the Road” is somewhat sub-canonical—also a tour de force, like Nabokov’s book, but considered more a literary phenomenon than a work of literature. On the other hand, it has had an equivalent influence. Nabokov showed writers how to squeeze a morality tale inside a Fabergé egg; Kerouac showed how to stretch a canvas across an entire continent. He made America a subject for literary fiction; he de-Europeanized the novel for American writers. Kerouac’s influence is all over Thomas Pynchon’s books: the protagonist in Pynchon’s first novel, “V.,” clearly alludes to Sal Paradise—his name is Benny Profane. Don DeLillo’s first novel, “Americana,” is Kerouac in spirit if not in style. John Updike scarcely qualifies as a Kerouac disciple, but Rabbit’s frightened flight by car in the beginning of “Rabbit, Run” is a kind of friendly, parodic allusion to the men of “On the Road.” And, as Howard Cunnell cleverly suggests in his edition of the scroll, “On the Road” might be called the first nonfiction novel: Kerouac’s book came out eight years before Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood.” It is certainly one of the literary sources of the New Journalism of the nineteen-sixties and seventies, the outburst of magazine pieces, by writers like Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion and Hunter Thompson, that took America and its weirdness as its great subject.

Books like “On the Road” have a different kind of influence as well. They can, whether we think of them as great literature or not, get into the blood. They give content to experience. Many years after my encounters with Ginsberg around the department water fountain, I took a job in Boston, two hundred miles from New York, and I ended up commuting there by car. I drove at night, so that the trip would not eat up the workday, and I often stopped for gas at a service area on the Mass Pike about fifty miles from Boston. It’s fairly high above sea level there, in the lower ranges of the Berkshires, and I would stand at the pump in the dark looking at the stars in the cold clear sky as the semis roared past and with the wind in my hair, and I liked to imagine that I was a character in Kerouac’s novel, lost to everyone I knew and to everyone who knew me, somewhere in America, on the road. Then I would get in the car, and, bent over the wheel, while the trucks beat on past me, and the radio crackled, the sound going in and out, with oldies from the seventies, I began the long drop down to the lights of Boston, late in the night, late in my life, alone. ♦